Wood 1 Wood 1

The invention of the wheel only makes sense if you connect two of them with an axle. And that only if you put anything on it to transport loads, a box that is only open at the top for free-flowing goods such as sand or grain, only

supports to the left and right for elongated goods such as wood. Both are mutually dependent, so the wheel is also dependent on the vehicle.

The wheel is unparalleled in nature. Not only that even tree slices can not be used with ony two saw cuts and a hole in the middle, but also that there is no such thing as a purely round shape. It would probably not be durable

enough for years of use because of an asymmetrical course of the annual rings.

However, thinner, straight trees or branches were probably used to transport heavy goods even earlier than 5,000 years ago. Such tools are said to have been used already in the construction of the pyramids, which took

place much later. Such aids must also have been used for the building of the huge stones of Stonehenge in southern England, because such are not found in the immediate vicinity.

We are probably already dealing with a combined transport here. Perhaps ships with such a carrying capacity already existed. Once loaded, a longer drive was a breeze compared to tedious rolling on previously ground

brought to the level. By the way, a land vehicle can do without wheels, namely with skids, if you accept a lot of friction or on e.g. snow or ice-covered ground.

Let's stay with the wheel, in this case made of a solid slice. If one assumes draft animals, which of course do not always have to be horses, the enormous weight of such bicycles may still be acceptable. However, if the

resulting wagons are pulled or maneuvered by people, they often perceive the load as too great and as a danger downhill. So you start early on to lighten the wheel at the point where it weakens the construction the least,

namely between the outer ring and the wheel hub.

The two remain still quite stable or oversized for a while, while wooden spokes in between not only ensure less weight, but also a little more aesthetics. They don't always have to be arranged strictly radially, they can also

quite straight touch the hub and land on the outer ring at the other end. Nevertheless, the first constructions of this kind seem to have shown the greatest wear in the middle between the rotating hub and the stationary axle.

And that despite the fat filling, which was still of animal origin at the time. That could have been the use of the first bushing and this is always a cause for astonishment for laypeople. Actually, this means the partner of a bolt.

Several bushings can also be attached to this, each of which makes a larger part rotatable in relation to it or the others. For better support, one part can also access to the bolt with two bushings, which can also be firmly

clamped in one of the rotating parts.

With our wooden hub on the basically fixed axle, however, a bolt would be out of place. Here the hub needs a wide iron ring that is firmly seated on it, on which a similarly fixed ring that is firmly connected to the hub can rotate

with a little clearance. What is happening here is called sliding friction and of course requires at least a grease filling, otherwise one ring will seize on the other. What is happening here is called sliding friction and of course

requires at least a grease filling, otherwise one ring will seize up on the other.

And then you will have searched for solutions for the outer ring, which wears out relatively quickly. First equipped with nails or leather, they finally ended up with iron, which also held the wooden ring made up of segments

together better. First equipped with nails or leather, they finally ended up with iron, which also made the wooden ring composed of segments held together better. Strangely enough, the part is also called a 'tire', which doesn't

mean so much springy properties, but possibly its possible substitution.

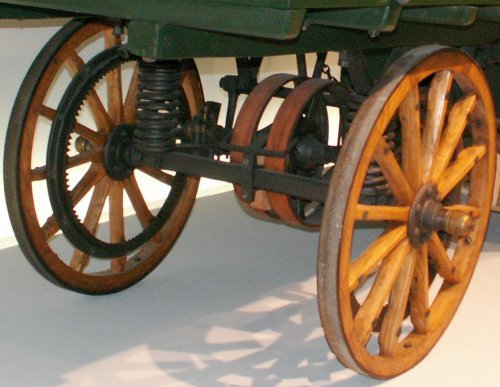

Although we might have been accustomed to one-axle chariots from the Romans, here is a replica of a carriage sprung with leather straps. The wheels are astonishing, which, apart from the design of the hub, can still be

found on the first Daimler truck at the end of the 19th century (picture below). Only the brake is different. If you look closely, you will discover an inserted crossbar on the rear axle. This was necessary downhill so that the heavy

vehicle did not endanger the expensive draft animals (horses).

Speaking of expensive draft animals. In addition to the one-axle chariots that reached up to chest height, the Romans also had such for people who could afford them. Incidentally, the technique of chariot construction comes

to a large extent from the Egyptians, so it is already a good 2,000 years old there. Particularly easy to maneuver chariots with iron spokes are also known. The start of the Iron Age is dated to around 800 BC.

In this context, the early chariot races from Greece may also be known. The rear wheel of the Nesselsdorf model II from 1900 (picture above) is intended to show how people tried to cope with the sometimes considerable

lateral forces, knowing full well that the spokes are the most vulnerable part of a wooden spoke wheel. Also, such wheels could be tilted slightly outwards at the top to allow the wheel to start slightly on the inside.

| Penny farthing with wooden spoked wheels from 1865 . . . |

kfz-tech.de/PKa1

| First Fiat model from 1899 with nicely shaped and lightly painted wooden spokes . . . |

kfz-tech.de/PKa2

| Pirelli pneumatic tires with wooden spoked wheels . . . |

kfz-tech.de/PKa3

| Wooden steering wheel from a 1913 De Dion Bouton . . . |

kfz-tech.de/PKa4

|